Everyone wants to be a creative

Design thinking is taking the world by storm. And no wonder - its potential is huge. But what is it, and why is creativity so vital to what might seem like uncreative tasks?

Design thinking is a human-centred approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology and the requirements for business success

– IDEO

McKinsey analysts hanging out with designers. Boston Consulting Group partners discussing the importance of experimentation. There’s a reason why formerly numbers-driven industries are embracing iteration, agile thinking and jobs containing the word ‘creative’. It’s called design thinking: a problem-solving strategy that seems more at home in the studio than the office. It’s likely to change the way we solve problems both big and small forever – and it’s now a big part of the ZIS experience.

Design thinking was first introduced at Stanford University in the 1960s as a way of teaching engineers how to approach problems creatively. Its ideas began to find their way into the business world, thanks in part to legendary design consultancy IDEO, founded in 1991 and headquartered in California. IDEO defined design thinking as “a human-centred approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology and the requirements for business success”. This problemsolving methodology then translates to a simple – though not necessarily easy – process.

In 2005, Stanford began teaching design thinking as an approach to technical and social innovation. Now, it’s routinely taught by prestigious universities – including ETH in Zurich – as part of their curriculum or as a stand-alone Design Thinking Master’s programme. The ideas it espouses are used in sectors from banking to car manufacturing and hospital design to computer game creation.

And it’s why ZIS now incorporates design thinking across its curriculum. “In very basic terms, all we’re actually doing is providing a problem for the students and a framework for how to navigate it,” says John Northridge, ZIS’s STEM Coordinator. “During a project, students have to use their prior understanding to try and tackle it, but at a certain point their prior knowledge hits a limit and they need to extend their understanding. If we have a process such as design thinking, we can start with the problem and we work our way through that problem by developing a real understanding of the needs and pain points of the people impacted by the problem.”

John uses the examples of students being asked to tackle the problem of sustainable food production in megacities, from which ideas of building floating farms emerged, with integrated aquaponics and renewable energy production. This, in turn, means students need to understand photosynthesis, water management and the circular economy, extending into other subjects such as mathematics and design.

One valuable aspect of design thinking is changing student mindsets to appreciate that failure is a real part of the process – to be more reflective on what we’re trying to achieve

– JOHN NORTHRIDGE, ZIS STEM COORDINATOR

“Having a built component in the project where possible means that students engage with their learning on a new level,” says John. “They are not just thought experiments. They actually have to design and build a solution to the problem.” He also points to opportunities closer to home, with a design thinking challenge set for Grade 12 students that aims to develop solutions to traffic management on the new Secondary Campus. They can use design thinking to generate campaigns that are designed to nudge behaviours towards more sustainable travel choices.

“Just going through the design thinking process teaches students valuable skills, such as teamwork, independent research, communication – and, vitally, how to fail,” says John. “One of the most valuable aspects of design thinking is changing student mindsets to appreciate that failure is a real part of the process and only serves to strengthen the final product. In many cases, there are lots of different solutions and no single right answer. It encourages us to think a little bit more and be more metacognitively reflective on what it is that we’re trying to achieve. I think that’s a valuable lesson for learning – but also for life.”

In April, ZIS ran its inaugural Design Thinking Event, initiated by the Board Committee on Corporate Partnerships as part of ZIS’s Strategic Plan. It brought industry partners together with students to tackle industry-specific challenges using the design thinking process. Each industry partner set a specific challenge to a student group, and a ZIS educator alongside a coach from Sparklabs at ETH Zurich supported them throughout. At the end of the event, each group presented their solutions to parents.

“Our group was assigned the ZHAW, and their question was: ‘How can we find better ways of living in a city?’” says Monica Meijer (Grade 12). “We went deep into defining the question and we ended up looking at more general solutions for all city dwellers. We considered all kinds of aspects, from availability of basics like food and transport to creating more sustainable cities. Our final idea was something small, but which could have a big impact on energy saving – a light switch which turns itself on and off when you walk in and out of a room.”

Monica says her main takeaway from the event was the importance of empathy in problem-solving. But, she adds, she’s also gained an insight into how the problems facing her generation might be approached. “In fact, I feel like I’ve seen the future. Ten years ago, design thinking wasn’t so important. Now, as challenges get more complex, I think it will be the way forward.”

I feel like I’ve seen the future. Ten years ago, design thinking wasn’t so important. Now, as challenges get more complex, I think it will be the way forward

– MONICA MEIJER, GRADE 12

ZIS DESIGN THINKING EVENT ATTENDEE

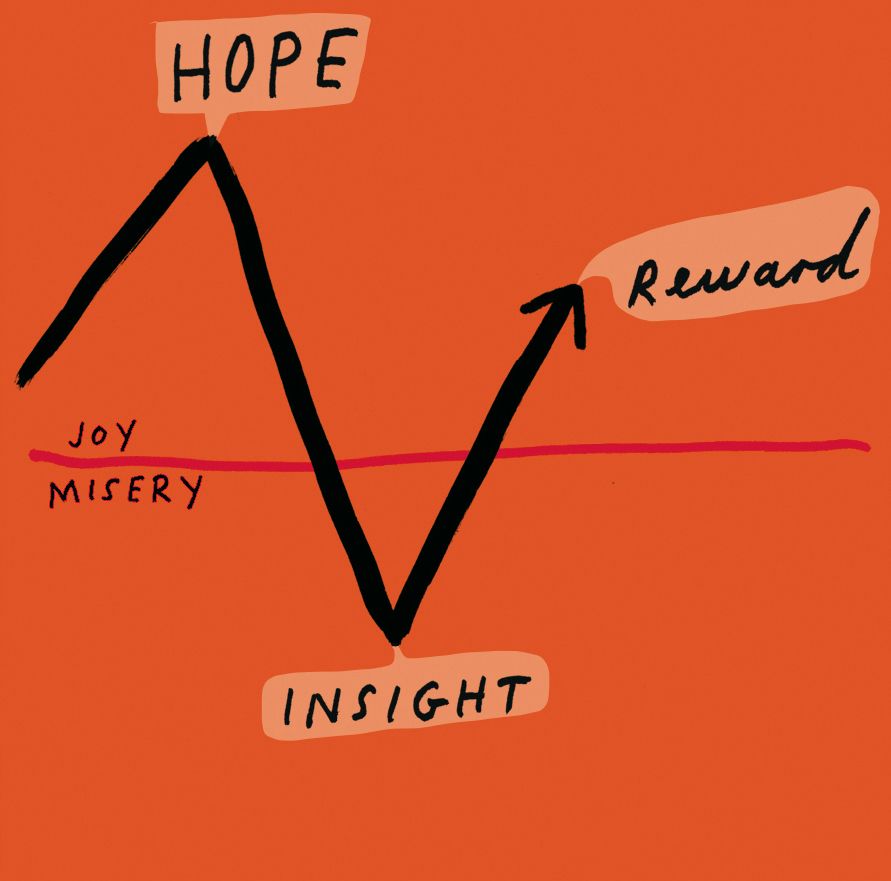

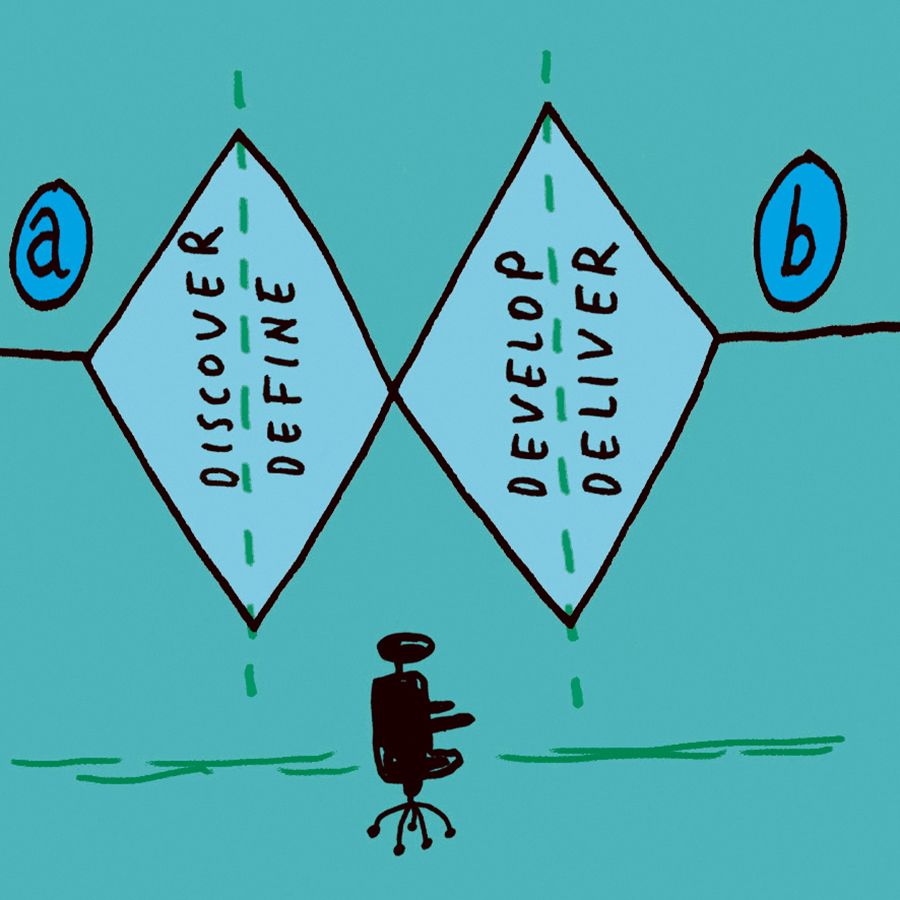

Marco Dönier, project manager for CSX Strategy at Credit Suisse, was at the event. “For me, design thinking is a toolkit and a beautiful approach for both business and for life,” he says. “It first enables me to empathise with a problem or with a situation. Then I need to define and understand the problem or the situation. Next, it’s ideation – coming up with a bunch of solutions that help me to solve a problem. And lastly, it helps me to prototype and test those potential solutions. It’s an iterative process: when something is not right, you can just step back and start over again. It’s an approach that helps me to find the best possible outcome.”

Conventional thinking produces a product or service that a client or customer must fit to their needs. In design thinking, it’s the other way around: the problem, rather than the product, comes first. This human-centred aspect of design thinking makes it very effective for innovation, says Kerstin Strubel, founder of the Lupo Marketing Training Company, alumni parent and former trustee.

Kerstin says that, these days, corporations regard design thinking as a core competency. And they recognise the value of a design thinking approach, not just to solve problems but also to boost collaboration. “Employees are trained to be creative in finding solutions collaboratively across different functions in the organisation,” she says. “For many companies this methodology is used in innovation departments, to come up with new products or services.”

In fact, design thinking, Kerstin says, is “totally industry agnostic”. It can be used to design a new car, define a new customer service for a bank, to build an app for an ecommerce business, or find a way to encourage people to recycle more. And its cross-collaborative ethos means it’s perfect for solving complex problems that can’t be overcome by one person, one discipline or one company department alone, such as reducing carbon emissions or driving the sustainability agenda. But its flexibility also means that it’s increasingly being applied in different fields, such as education.

“The way I approach learning is that we should not be looking at subject-specific problems,” says John. “In the world of work, you don’t use English on one day, then maths on another. We should be bringing subjects together into meaningful projects, looking at real problems that students can see and experience in the real world.

“It could be big challenges, like global warming, or smaller ones, like getting more students to walk to school. But to solve a problem, you must look at it with a different mindset that reaches across different subjects, from maths to geography to IT. ‘What’s the problem? How can I find out more about it? What materials might I need to fix it? Who are the experts in this field who can help tackle this problem?’”

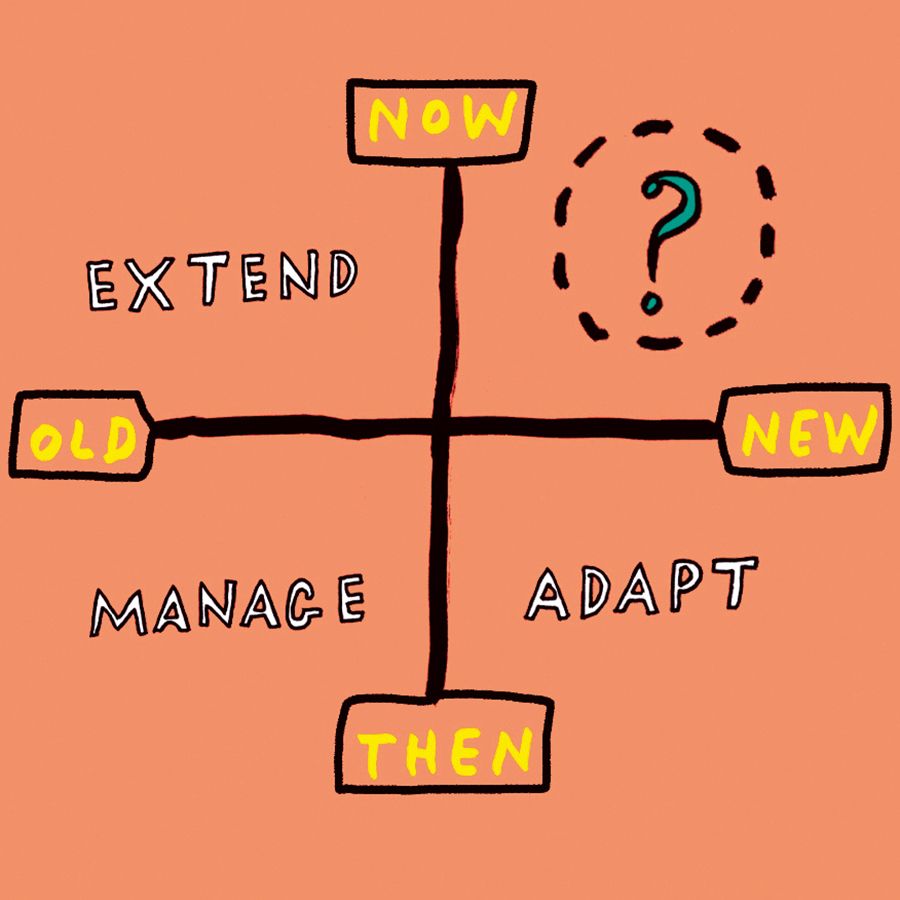

Marco points to two key tenets of design thinking: ‘fail fast’ and ‘kill your darlings’. “Say you design what you think is the best, most comfortable running shoe. You test it with professional runners. They say it’s OK, but not great. Rather than arguing, you listen to what the professional runners have said, and you immediately adapt your product.”

Design thinking has the power to change the world for the better – but it’s still a relatively young methodology. And ZIS students, says Kerstin, are perfectly placed to take it forward. “It will truly set them apart when they apply for universities or jobs in later life. It enables them to effectively work together in a team and keep a creative and solution-oriented mind. And it will enable them to be leaders for positive change in the future.”

Design thinking is totally industry agnostic. It can be used to design a new car, define a new customer service for a bank, to build an app for an ecommerce business, or find a way to encourage people to recycle more

– KERSTIN STRUBEL, PAST TRUSTEE