Sustainable Futures

We all have a role to play in tackling real-world issues, and ZIS’s focus on sustainability – a priority for the coming year – is linked directly to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

More than 150 workers install photovoltaic panels at the Cimarron solar plant in Colfax County, north-eastern New Mexico. Launched in December 2010, it is one of the largest utility scale solar power plants in the US.

Harvest might be the high point for all farmers, but for ZIS’s Kindergarten students it is extra special. That’s because when Kindergarten students tuck into freshly-made soup and pesto, most of their meal will have been grown just inches from their table.

The home-grown food is part of a quiet revolution taking root across the school. Over the past few years, raised beds have sprung up, parents have rolled up their sleeves and new plants – from beetroot and berries to peas and potatoes – have flourished.

Today, the Lower School garden has evolved from a great outdoors space into a green classroom where students are gaining vital understanding about their future – and the planet’s.

The outdoor classroom is part of the school’s sustainability programme and the brainchild of ZIS Sustainability Coordinator Kristie Lear. “I’m a big picture thinker, because to solve sustainability challenges you need to look at the whole impact,” says Kristie. “You can’t solve climate change if you’re not addressing poverty and infrastructure, for example, and you can’t solve hunger if you’re not looking at climate change.”

As a result, her approach at ZIS has been to unearth everything the school is already doing for sustainability – in its curriculum, community and business practices – and build on those strengths. “You can’t do sustainability justice simply by teaching it in a science class or running an annual event. It’s a mindset and a conceptual framework for making decisions,” she says. “For me, the priority is to develop a sense of community around real-world issues. We have a real opportunity to work together as parents, teachers and students for systemic change.”

Five years ago, as chair of the sustainability committee, part of the ZIS Innovates initiative, Kristie was tasked with developing a programme that would put sustainability at the heart of ZIS. Inspired by Berkeley’s Edible Schoolyard Project, she began by transplanting its model of edible education from California to Zurich. “Before I jumped in, the garden formed part of a six-week Grade 1 unit,” she explains “But that’s not how nature works, so I decided to make more use of the space.”

"You can’t do sustainability justice by teaching it in a science class or at an annual event. It’s a mindset – a conceptual framework for making decisions"

In response to the uncertainty of future energy needs, Ratcliffe-on- Soar in Nottinghamshire, England, is expanding both its production of electricity and the stockpile of its coal onsite.

Now integrated into Kindergarten and Grade 1 learning, the outdoor classroom is being used for teaching units on plants and animals, food systems and the school community. Together with visits to local farms and forests, the garden helps students learn where their food comes from, and how ecological systems sustain us.

“The garden creates lots of opportunities for teachers and kids,” says Kristie. “Planting and caring for seeds gives children ownership of the space and teaches them indirectly to care for nature through their experiences of nature.”

But sustainability is about more than ecology. In 2015, the United Nations adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which together form a blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet. The goals are wide-ranging and ambitious – from zero hunger and quality education to climate action and responsible consumption and production – and they are all interconnected.

The UN wants to achieve the sustainable development goals by 2030 – a big ask, with a hefty price tag. According to the Brookings Institution, doing so requires mobilising $5-7tn per year. By contrast, the OECD calculated that public spending on development aid amounted to $146bn in 2017 – just two per cent of the target. Even with philanthropy (which amounts to an estimated $10-400bn) the shortfall is huge. Nicole Neghaiwi, Class of 2006 (2000-06), is focused on finding ways to bridge that funding chasm. She works as an impact investment analyst for a major Swiss bank, work she believes makes a difference but which came to her by accident.

UN SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS

ZIS is taking a proactive approach to support the UN’s SDGs, part of its 2023 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The SDGs are “an urgent call for action by all countries in a global partnership. They recognise that ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality and spur economic growth – all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests.” The goals are:

01 NO POVERTY

02 ZERO HUNGER

03 GOOD HEALTH AND WELLBEING

04 QUALITY EDUCATION

05 GENDER EQUALITY

06 CLEAN WATER AND SANITATION

07 AFFORDABLE AND CLEAN ENERGY

08 DECENT WORK AND ECONOMIC GROWTH

09 INDUSTRY, INNOVATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE

10 REDUCED INEQUALITIES

11 SUSTAINABLE CITIES AND COMMUNITIES

12 RESPONSIBLE CONSUMPTION AND PRODUCTION

13 CLIMATE ACTION

14 LIFE BELOW WATER

15 LIFE ON LAND

16 PEACE, JUSTICE AND STRONG INSTITUTIONS

17 PARTNERSHIPS FOR THE GOALS

sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs

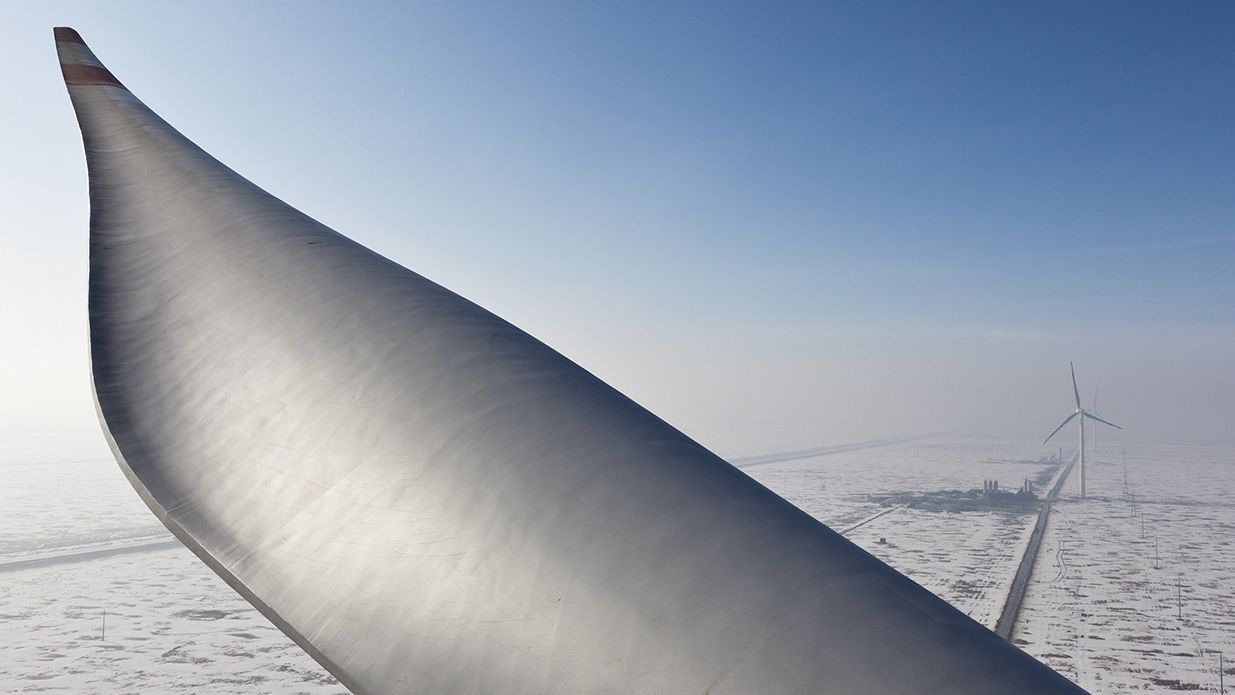

A view from the top of a wind-turbine nacelle (the part of the turbine that houses the components to transform the wind’s kinetic energy into mechanical energy) on a wind-farm in Inner Mongolia.

“Impact investing is a type of sustainable investing that seeks to generate measurable environmental or social impact in addition to financial return. That could be investing in social enterprises, for example, whose business model is addressing a specific social or environmental challenge,” Nicole explains. “It seeks a dual bottom line – the assumption being that the two are not mutually exclusive.”

What makes impact investing crucial is that without using private wealth, we cannot fund the SDGs. “We used to see this as the domain of the public sector, but it’s increasingly obvious that with traditional finance, we’re just not going to make it,” she warns. “If we look at private wealth – there’s $280tn in private savings out there – the potential is huge. Mobilising just two per cent of that would overcome the funding gap.”

Nicole has been passionate about sustainability since her teens. At ZIS she was inspired by Upper School Social Studies teacher Paul Doolan and was active in the Model UN, Amnesty International and several product boycotts – but a career in banking was not on her radar.

“To be honest, it was a bit of a mistake. I did a degree in Development Studies at Queen’s University in Kingston, Canada, and it never occurred to me to work in a bank,” Nicole says. “When I came back to Switzerland after university, I found that – unsurprisingly – aid organisations didn’t want to send an inexperienced 21-year-old into the field.”

Instead, she got a job with an environmental, social and corporate governance data company and discovered that, despite being far removed from the frontline, her work could have significant impact. When she wrote a report on palm oil that encouraged a pension fund to demand that the producer improve their poor practices, the penny dropped. “I realised that what I was doing was probably changing more lives than working in the field,” she says. “That was my ‘eureka’ moment. It led to where I am now.”

Generating change by moving massive companies minute distances is something Julian Meitanis, Class of 2000 (1995-2000), recognises well. A senior consultant at Zurich-based Sustainserv, he helps large corporations as well as small firms and NGOs build long-term value by identifying the risks and opportunities they need to mitigate or take advantage of.

As a sustainability consultant, he believes that companies need help on two key fronts: keeping up with an accelerating pace of change; and dealing with increasing complexity. “We look at where companies can create a positive impact – environmental, social and economic – at the same time as building better products and better relationships with their clients, communities and stakeholders. Public perception can make or break companies,” he explains.

Ten years ago, when he first started working in sustainability management, the business landscape was very different, says Julian: “Then, sustainability was rarely an integrated part of business. The discussion is moving forward now; sustainability is driving decision-making, governance and business strategy. We’re at a crucial point.”

Julian’s own ‘eureka’ moment came when he read Paul Hawken’s Ecology of commerce: a declaration of sustainability. First published in 1993, the book argues passionately that as well as causing the greatest environmental abuses, businesses also have the greatest potential for solving our sustainability problems.

“I remember reading it, and the analysis is brutal. Our economic models are not in harmony with the world, which made me realise that we faced a lot of problems if we continued down the same track,” he says. “In the past 10 years, it’s become very apparent that business as usual is no longer an option.”

Grade 12 student Nicholas von Klitzing is busy spreading the sustainability word among fellow students through Project Green, the Upper School’s sustainability club. Established in 2012, Project Green’s mission is to improve the school’s sustainability, and every year students get together for a brainstorming session to identify key issues they want to tackle.

Last year’s projects are diverse – from plastics and ‘plogging’ (a cross between jogging and litter picking) to cycling and car pools. Project Green teamed up with the school’s athletes to organise a plogging event, which involved the cross-country team cleaning Zurich’s streets while out on their training run. They also organised a bike-to-school challenge, using rewards to persuade more students and staff to cycle to school. But their most ambitious project has focussed on single-use plastics, and they used the school’s carbon offset fund to install a carbonated water dispenser so students can fill up their own bottles for free.

It’s a good illustration of his belief that sustainability is everyone’s responsibility, and that his generation can rise to the challenge. “The most important thing is establishing good habits. Our behaviour as children shapes our habits as adults, so we’re trying to change as many students’ habits as we can so that we can live more sustainable lifestyles,” he says.

“Individuals matter on a grand scale – that’s what people my age sometimes don’t understand, and it makes me sad, because individual changes ultimately bring global changes. Lots of students say they can’t make a difference. We want to challenge that mindset so that we can get meaningful change.”